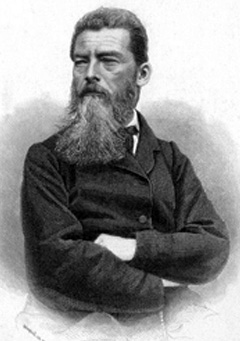

Ludwig Feuerbach (1804-72)

Ludwig Feuerbach (1804-72)

If you've always thought of Feuerbach as a straightforward atheist who saw God as no more than a projection of humankind's best qualities, think again. He's a remarkable thinker, and can contribute significantly to our thinking about 'God' in today's secular world.

He also offers some great and provocative one-liners:

'To think is to be God.’

Not quite sure of that - but it's one step on from Descartes!

'For religion God is not a matter of abstract thought, - he is a present truth and reality.’

Hence, all arguments for the existence of God miss the point, and are a product of 'vulgar empiricism'.

The notes that follow were written a couple of years ago, and I've been revisiting them in preparation for the new book.

Thoughts on re-reading Ludwig Feuerbach's 'The Essence of Christianity' (1841)

Ludwig Feuerbach’s view of religion tends to be summed up as ‘projected anthropology’ or some such phrase. Along with Marx and Freud, he is generally held to be one of the detractors of religion, reducing it to the human and thereby depriving it of its power, mystery and supernatural beliefs. God is seen as the highest aspirations of Man, projected out onto the universe.

But re-reading his The Essence of Christianity, I have been struck by just how positive and useful his analysis is, and how he makes something of a bridge between the older tradition of natural religion – which has its focus primarily on concepts to be believed – and the practice of actual religion.

First of all, as the basis of all that he has to say, there is the conviction that religion is distinctive and positive human quality. His opening sentence:

‘Religion has its basis in the essential difference between man and the brutes – the brutes have no religion.’ (This and all quotes is from the translation by George Eliot in 1853.)

And that difference is consciousness, the ‘feeling of self as an individual’ so that ‘man has both an inner and outer life.’

He therefore sees ‘feeling’ as the key to religion. ‘Whatever is God to a man, that is his heart and soul’ so that ‘Consciousness of God is self-consciousness, knowledge of God is self-knowledge.’

The problem is that we generally see the self as something separate from the world and separate from the ‘feelings’ that it experiences – in fact even that way of putting it, sets feelings apart. What Feuerbach seems to be working towards is a sense that you (and God) are exactly those feelings of wonder and so on that constitute religion. Once feeling is separated from self, Feuerbach suggests that, in bondage to what he calls ‘vulgar empiricism’ and incapable of appreciating the grandeur of feeling, we slip back and ask if God exists or not. [And, I would suggest, we equally start to ask whether we exist or not, with vulgar empiricism leading to the nonsense of identifying the self with the physical brain.]

Feuerbach is wonderful at one-liners; a century later he would have been a natural for the advertising industry! On p40 he says:

‘Existence out of self is the world; existence in self is God. To think is to be God.’

But in case you assume that the result is a universal, non-anthropomorphic concept of deity, he adds that such a God has no more significance for religion than a fundamental general principle has for special sciences. It is ‘merely the ultimate point of support.’

What this works towards is a sense that religion is cultivating a sense of self within the world in a way that is entirely positive and distinctively human. There is the sense that finding peace with God is a matter of becoming at one with one’s true nature. In other words, he is to find God in himself.

I was surprised at just how much of the book Feuerbach devotes to specific Christian beliefs and teachings, and indeed of the human and felt dimension of the sacraments. But towards the end, he delivers what really is a crushing argument against those who attempt to prove the existence of God:

‘The contradiction to the religious spirit in the proof of the existence of God lies only in this, that the existence is thought of separately, and thence arises the appearance that God is a mere conception, a being existing in idea only…

but he wants to emphasise that, for religion, God cannot just be a concept, a thought…

‘for religion God is not a matter of abstract thought, - he is a present truth and reality.’

In other words, he is affirming God as a living experience – but doing so NOT in the sense that there is an ‘external’ God of whose existence one is convinced, but that God is essentially a feature of one’s own feeling life.

So he is able to say:

‘The proofs of the existence of God have for their aim to make the internal external, to separate it from man.’

He does not see God as having an existence ‘apart from belief, feeling and thought’, concluding:

‘God is not seen, not heard, not perceived by the senses. He does not exist for me, if I do not exist for him; if I do not believe in a God, there is no God for me.’

He recognises that a consequence of there being no ‘sensational existence’ for God is atheism. Everything else that exists does so because we can sense it (or – I would add – consider it something capable of being sensed), and the ‘vulgar empiricism’ that dominates our lives takes this as the only genuine meaning of existence. So Feuerbach is able to say that, if I do not raise myself above the life of the senses, God has no place in my consciousness. He exists only in so far as he is felt, thought and believed in. At one and the same time, God therefore exists and does not exist. He is real, but not empirical.

The problem is that, once religious people try to express the meaning of God, this feeling and idea they have, they start to project it as having a separate existence.

‘But when this projected image of human nature is made an object of reflection, of theology, it becomes an inexhaustible mire of falsehoods, illusions, contradictions and sophisms.’ (p123)

You can’t get much more critical than that, but in the end Feuerbach wants to reclaim something of value from all the sophistry. He sees the essence of religion as the identity of the human and the divine, but the forms that religion takes have exactly the opposite effect, namely to separate man and God. Rather, he wants to point (in a most conventional religious way) to the role of love: ‘Love identifies man with God…’ (p247) and then contrasts love with faith:

‘Love has God in itself: faith has God out of itself; it estranges God from man, it makes him an external object.’

And another of those wonderful one-liners:

‘The secret of theology is anthropology.’

It seems to me that the implication of all this – which is surely good theology – is that God is encountered in and through loving relationships, not because he endorses them, but because he is them.

Far from offering a negative critique of religion, Feuerbach makes a positive contribution here, and one that makes explicit what is implicit in much religious language, namely that the term ‘God’ should be used for an experienced reality, not for a possible external entity. The very idea of asking whether God exists implies a failure to understand what the word ‘God’ means.

Marx and Freud both saw religious belief as a matter of projection, whether it is of a future compensation for present troubles, or a replacement for a lost father figure. Superficially, Feuerbach offers the same line of thinking, with God as a projection of the highest human ideals. But that would be to miss some of the key ideas in The Essence of Christianity, which is – as the title implies – an attempt to get to what religion is fundamentally about.

A deist might say that belief in God is a matter of seeing structure, meaning and purpose in the universe. But surely that does not add anything to the statement that there appears to be structure, meaning and purpose – there is no added extra corresponding to God. What a glib atheist assumption misses, however, is the further point that reality is essentially something in which we live and with which we engage, not something about which we speculate.

Clearly, if all Feuerbach meant was that theology could be replaced by anthropology – an attempt to speak of an objectively existing God replaced by objective statements about humankind, then his analysis does not do justice to what religion seeks to achieve – namely a deeper engagement with life, rather than an additional layer of speculation about life.

Mel Thompson, June 2023